RPG_Progression

Analysis of what is a progression system and how to implement it in a RPG video game.

Project maintained by AndyCubico Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

This is a page created by Andreu Nosàs Soler, student of the Bachelor’s Degree in Videogame Design and Development from CITM. It is an introduction to progression systems and a guide in how to create them in a RPG.

Introduction

Most players are familiar with the concept of difficulty progression, the fact that games should get harder over time. However, difficulty is only one portion of the progress of a game, and there are other elements that require to be structured and managed carefully so that the videogame can provide the user with a compelling and enjoyable experience throughout the gameplay. With that in mind, let’s see what Gameplay progression really is. This are a couple of definitions of the term that we can get from Oxford Languages:

noun

1.forward or onward movement towards a destination.

"the darkness did not stop my progress"

2.development towards an improved or more advanced condition.

"we are making progress towards equal rights"

verb

1.move forward or onward in space or time.

"as the century progressed the quality of telescopes improved"

2.develop towards an improved or more advanced condition.

"work on the pond is progressing"

All of these definitions could be applied to video games, since both the pattern of advance and the act of moving towards the ultimate goal of beating the game are key to creating an enjoyable experience for the player. This pattern of advance will keep the player in the game loop if done correctly.

Progression in video games can be divided into the three following categories depending on which is the focus:

1.-Player progression: improvement of the skill and knowledge of the game that is being played. Many action based games are designed around this concept.

After dying many times, in souls games the player gets better and can defeat the challenge that he is facing.

2.-Character or abstracted progression: our character becomes stronger outside of the player’s skill. RPGs are the best example of this (leveling up)

3.-Game progression: moving through the different levels and areas of the game until reaching the credits.

There are also 5 key elements of gameplay progression that we have to keep in mind in order to create a good progression system:

1.-Game Mechanics: they directly affect the control complexity and the learning curve of the game. There are two ways to create this progress:

- Gated access: make some mechanics unavailable initially. Metroidvanias are a great example.

Double jump feature in Hollow knight is unlocked later in the game

- Directed gameplay: all mechanics are available from the get go, the gameplay will entice the players to use them as the game goes on.

In souls games you have all the abilities tied to the character from the beginning.

2.-Experience duration: how much time it takes to finish a level, stage, mission, which can be increased with mission distance and opponent difficulty.

3.-Scene rewards: create the levels of the game in a way that new visual rewards like exciting environmental wonders or fancy visual effects are staggered at a pace that keeps the player invested in the game.

In Elden Ring, after defeating the first demigod, Elden Ring shows us how much is left to explore.

4.-Practical rewards: unlocking new content pieces or upgrading our characters that directly change, expand and improve how the game is played.

5.-Difficulty: how hard are enemies to beat and also very important, how much risk the player takes in order to beat it with respect to player health (death), weapon durability, use of items (health potions).

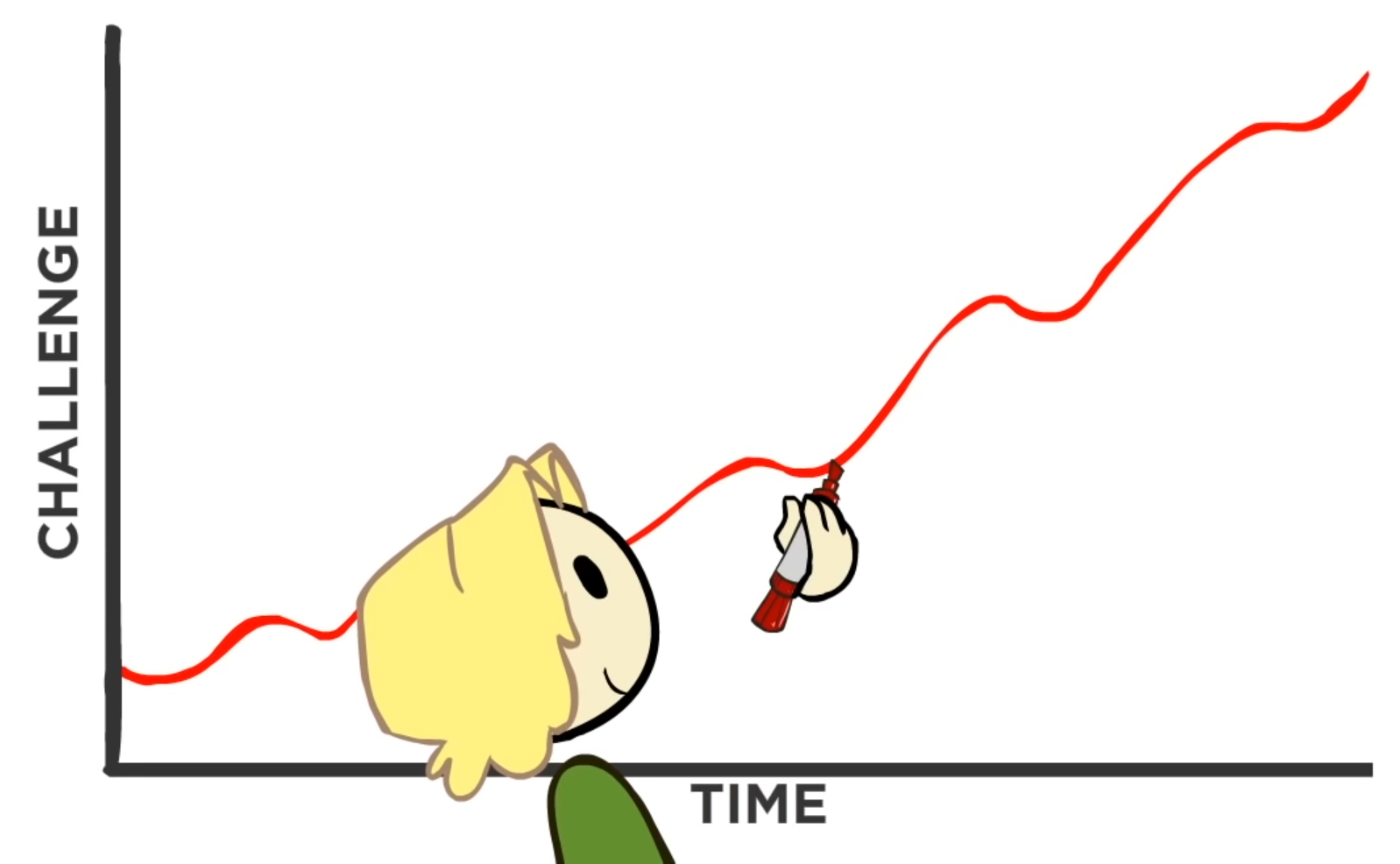

If game designers do not structure correctly all these elements, they may overwhelm the user with too much, or boring them with too little so they stop playing. The concept that defines this matter is the Flow. Flow is a mental state of operation in which the person is fully immersed in whatever he is doing, with a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and success in the process of an activity.

It is key to the design of the game to keep the player on the flow zone, otherwise our users will stop playing the game. A good progression system should motivate players to keep playing, no matter if they are winning or losing. As long as the player is moving forward, they will be motivated to keep playing, otherwise they will be frustrated and stop playing the game.

Type of progression in RPGs

Level based progression:

The most classic one, players gain experience points when defeating enemies, leveling up their character when they reach a certain amount of points, becoming stronger when doing so. The following levels usually are harder to get, so it is harder to become stronger as the game goes on. Most JRPGs and CRPGs use this system.

Training progression:

The player increases their power when they perform certain actions or use specific tools to perform these. Skyrim is the best example of this kind of system, where running or killing enemies with a given type of weapon increases the proficiency with it.

Skill tree progression:

players can customize how their character develops with a skill tree, where they can allocate earned points to gain different kind of abilities, creating a build path to pursue (similar to previous one but it is important to note how you obtain the resources to advance through them and how they are created).

Equipment based progression:

Player focuses on finding better armor and weapons to upgrade their character, at the cost of giving up whatever they had beforehand. A great example of this is the MH saga.

Most RPGs integrate these systems together, FFIX keeps the traditional xp leveling systems of RPGs and introduces the equipment based progression with training progression, where you have to equip certain items to gain cool new abilities, and when you have used them enough you can get the abilities without the equipment needed.

Math in progression systems

As we have seen, the most typical way in RPGs to create a progression system is with level progression requiring a given number of experience to reach each level. In order to see how to create such a system, we will see 4 different types of functions where we plot the values of the experience required(y) and the current level(x). With these, we will be able to define how much experience (and time) the player invests in the game in order to gain a level. This are the curves that we will see:

Example of progression curves: Linear (blue, A), logarithmic (orange, B), quadratic (red, C) and exponential (green, D).

If our experience curve is linear, each level will require the same amount of experience than the previous one.

Linear curves for the purpose of determining the xp required to level are not used given how boring they can be, since they are predictable and can feel grindy. However, they can be used to make the progress of some stats with each level increase.

If we use an exponential curve or polynomial, the player will need more experience to reach the next level that the previous one, and therefore the player levels-up slower at the end game.

And if we use a logarithmic curve, at every level we will need less experience than the previous level. The exponential and plolynomial are the most popoulars in RPGs, but you can choose whichever you see fit for your gameplay ideas.

Mind that exponential and polynomial curves have a subtle difference, while the exponential curves grow at the same ratio all the time (having astronomical values at later levels), the polynomial cruves growth actually gets smaller as the level increases. In exponential progression systems we will have to raise the rewards to keep up with the level required to get them (easily exploitable, since you can kill a harder boss and get so much xp that you rush through the game). Polynomial systems they can get grindy since and repetitive since the differences at higher levels are too subtle.

Examples:

- World of Warcraft, we have a formula for the experience required to level up at a certain level:

Where diff is a difficulty factor Where diff if a difficulty factor, MXP is the basic experience given by a monster of level L and RF is a generic scaling factor. This formula start as a quadratic experience curve and then explode into exponential (thanks to the Diff formula).

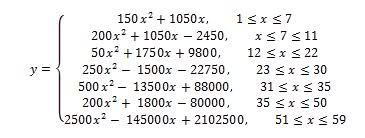

- Diablo 3, the formula varies depending on what threshold of levels is the user:

- Dreamcast game Armada (Metro 3D, 1999), uses the formula of 8 x (current level)^3 to determine the XP requirements.

Game loop and avoiding repetition

In order to have a good progression system and keep the flow of the game, it is very important to try to hide the game loop, that is, avoiding repetition. We should avoid introducing grinding in our game, where the player’s ability to progress is reduced to a few set options, and everything else will not move them forward. When players are forced to make a number of repetitive tasks just to collect enough points to level up, that is usually not fun for them. The player’s actual skill progression is not accurately tied to in-game progression. Adjust the difficulty level accordingly to avoid this kind of situation. One interesting way of tackling this problem is the level progression of chrono cross, where you only level up when you defeat the bosses, earning also stars for the sense of reward, allowing you to become stronger and advance to the next level.

We should also not be aiming to create what is called skinner boxes, psychological traps designed to keep us playing the game. Progression systems don’t need to be skinner boxes to be good. Progression systems should be part of the experience of the game, and not something merely created to keep the player playing the game, adding play hours and no content. Progression systems can add a long-term strategic component to our game. Most decisions that the player makes while playing are pondered in brief moments, but with a great progression system we can give the player the opportunity to plan out and contemplate these decisions for hours or even days (planning builds). An example of this could be the talent tree in World of Warcraft:

Anyone who has played an MMO knows how much time they can spend thinking about a build, to maximize damage output or be the tankiest character in the game. This adds a lot to the game, since you can have something to brainstorm about even when you are not playing the game.Be mindful of rewarding the player for thinking through the strategic conundrum that you are presenting, and a way to backtrack if they are not happy with the results of their build (re-spec).

Progression systems can also be created in such a way that the player shapes their learning curve and complexity of the game. That can be done with gated access to the game mechanics, introducing the elements one by one, allowing the player to familiarize with the given mechanic and get comfortable with it before moving on to the next one. Unlike tutorials, the player has control over how long each step of the learning curve takes, since if they have completely figured out the mechanic, they will be more efficient doing the challenges related to it, making them progress faster towards the next one.

A progression system can also enhance your narrative, for instance, faction progression, where actions you take affect your alignment with a faction in the game’s world.

Mass Effect’s reputation system is a great example of this.

Game Balance

We will begin this section with an example of how to balance the party members of a classical RPG and see what problems we could have.

Character balance

This will be the base stats of our main character Squell at level 20:

Strength: 50

Speed: 25

Stamina: 40

Spirit: 20

Defense: 40

Magic Defense: 15

Then we will create what are called the Derived Stats, the meanings of the base stats used to determine the effectiveness of them in battle. In this case they would be the following:

Attack Power

ATB Speed (time until next turn)

Dodge %

Hit Points

Magical Power

Physical Damage Negated (%)

Magical Damage Negated (%)

Determine Attack Power

In order to determine the attack power of Squell, we will multiply Strength by a constant of 10, since RPGs usually have a big number to show damage.

Attack Power = Strength * constant = 50 * 10 = 500

To make it less boring we could add some variance:

Attack Power = (Strength * constant) +/- 10% = 500 +/- 50 = 500 or 450

Now, Squells’s Attack Power will be somewhere between 450 and 550.

Determine Seconds Per Turn and Dodge %

This are based on speed, in this case since this stat should not increase too much throughout the game (otherwise it would be too powerful), we can divide it by the current level, getting a Speed coefficient.

Speed Coefficient = Speed / Level = 25/20 = 1.25

With this, our character with 25 speed at level 20 would have 1.25 speed coefficient. We will make a table to see if it makes sense and is not too exploitable.

Looks good enough, now we feel comfortable calculating Squell’s Time until next turn (ATB speed), that is, the time between turns. This value should go down (the faster the character the faster he gets the turn back), to do this we will divide a constant by the speed coefficient.

We will use 15 as our constant, but you can choose any number you like. A higher cosntant will mean more time between turns (slower pace of the game).

Seconds Per Turn = constant / Speed Coefficient = 15/1.25 = 12

Dodge % is easier to determine - just multiply the Speed Coefficient by a constant. Your only limitation would be to pick a reasonable constant, since accidentally choosing a large one would result in a very big Dodge Rate, which would be quite bad gameplaywise.

Dodge % = constant * Speed coefficent = 10 * 1.25 = 12.5

The Rest

We can use similar equations to figure out the rest of Squell’s derived stats. For instance, Stamina could be converted to Hit Points merely by multiplying it by a constatn. We would obtain the following table:

Balancing party members

Now let’s create a second party member, a mage called Riona with the following stats at level 20:

If we want to balance our characters, we will have to take a look at their DPS. Let’s compare them:

Squell’s DPS = Attack Power / ATB Speed = 500/12 = 42.7

Riona’s DPS = Magical Power / ATB Speed = 500/10 = 50

Based on our calculations, Riona’s DPS is 50 to Squell’s roughly 42, pretty much in balance. However, we have to acknowledge the fact that Riona has MP to use his damaging spells, whereas Squell does not (he just attacks). And some of Riona’s spells will be stronger than others. Thus, we cannot calculate her DPS using Magical Power alone. Instead, let’s delve a bit deeper.

Spells

With magical power we will determine the value of each individual spell. We will consider three kinds of spells: fireball 1 (single target and cheap to cast), fireball 2 (with higher mana cost and damage than fireball 1), and meteor (area of effect).

Assuming a Magical Power of 500, the Power and DPS of each spell will function as follows:

Note that fire 2 costs three times more than 1 and not 2, it would be too efficient, but you can make it cost twice, test and see how it goes. We can also see that Meteor is only useful against multiple enemies We will divide the damage of each spell by its ATB speed to get the dps, and by its mana cost to get the damage per mana point.

Riona’s Dps could be obtained by multiplying average cost and DPM, getting around 100 (6.67 * 14.86), but we have to remember that her mana pool is limited, and his DPS will drop by 80 percent if he has to use basic attacks (Attack power divided by ATB, 200/10).

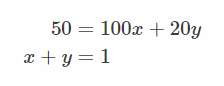

We know that Squell’s base DPS is 50, and that Riona’s is approximately 100 when she has MP and 20 when she does not. In order to figure out the perfect ratio of magical to physical attacks to be equal, we use the following system of equations:

y = 5/8 and x = 3/8 where y is the time that she has to be with Attack damage and x the time that she can cast spells.

This means that in order to both have the same damage output, Riona would have to be 5/8 time (around 60% of the time) out of mana, which means that she is a little bit overpowered.

We should tinker with the previous values in order to balance it more, or leave as it is if that is our goal. Consider this when blancing a your RPG:

- What are my base stats? What are my derived stats?

- Do the party members fall under specific class categories? If so, what are they?

- What kind of numbers do I want to see on screen - big ones or small ones?

- How much of a factor do I want randomness to play?

- Is the scope of my game realistic, or will I end up spending months balancing my game?

Another thing to keep in mind are break points, places in your game where major experiential difference occurs based on minor mathematical differences. In a standard RPG, we could have the case where our character does 100 damage per hit, and the enemies in the zone have 150 hp, this would mean that it takes two hits to kill them. We will consider that when you level up, damage increases by 20 (linear progression of the stat). At level 4, you would have 160 damage, making that you can one shot the enemies, making that the challenge and difficulty of this zone dropped to the floor. It also happens when you can cast your spell twice as much or you are fast enough to always fight first.

Breakpoints are not the same as power spikes, intentionally inserted mechanics that give the player a larger than normal boost of power when they reach a certain point in the game. A great example could be D&D’s spells and abilities, which get more powerful at a certain level.

This gives a good sense of progression, getting you excited to reach new levels. It is important to differentiate the power spike from the breakpoint, since one happens by your choice and the other from unexpected problems of the math of your system. In order to predict or control these breakpoints, you will have to thoroughly test your game and consider if they are really intended power spikes or mistakes from your mathematical system of progression. In the case mentioned before of one shoting the enemies, you could make that the rewards at that level in that zone get really bad, so that the player should move forward from that point.

Conclusions

- Be mindful of the different ways you can create progression

- Mix systems so that the game feels varied and fun to progress through

- Avoid repetition and grinding so that the player does not get bored.

- There is not one way to create an experience curve, do the one that suits your game better.

- Playtest the game many times to see if there are any breakpoints and the game is generally balanced.

Template

References

- Break Points - Balancing the Math with the User Experience - Extra Credits

- Progression Systems - How Good Games Avoid Skinner Boxes - Extra Credits

- Robert DellaFave - Balancing Turn-Based RPGs

- Av Thomas KL - The problem of repetition

- Josh Bycer - The dangers of grind in game design

- Josh Bycer - Understanding progression models in game design

- Gustavo Tondello - Level Up! The role of progression for gameful design

- Davide Aversa - GameDesign Math: RPG Level-based Progression

- Will Luton - THE MATHEMATICS OF GAME BALANCE

- Chris Bateman - Mathematics of XP

- Megan Smith - 10 RPGs With Equipment-Based Progression

- Rena Darling - 8 Most Unique Leveling And Progression Systems In RPGs

- Mike Lopez - Gameplay Design Fundamentals: Gameplay Progression

- RPG Progression Systems by Adrián Font